Speaking at Thailand’s first event to bring innovators and policymakers from around the world (PIX), Gina Belle, the Director & CEO of Chôra Foundation, provided a comprehensive overview and deep dive into the Policy Approach to innovative policymaking. Having worked with NGOs, the UNDP, and other institutions, their approach reinforces the importance of exploring, collaborating, learning, and maintaining holistic overviews of large-scale initiatives.

The Chôra Foundation is a Dutch non-for-profit organization which was established to develop and support strategic innovation and innovative systems transformations for social systems (agencies, companies, cities, or nations). With their unique approach, Chôra allows social systems to be equipped with innovative tools and knowledge to help it be ‘different’ and more resilient in areas such as social impact, financial systems, climate innovation, and social services. The framework redefines the scope of social systems across a 3-step process starting with assessing the problem, then facilitating learning (portfolio), before providing differences in the form of a budget of possibilities (impact). These budgets allow social systems to engage novel policy solutions making it more adaptable to complexity and accelerating system transformations.

Background to Portfolio Approach: The Problem of Complex Problems

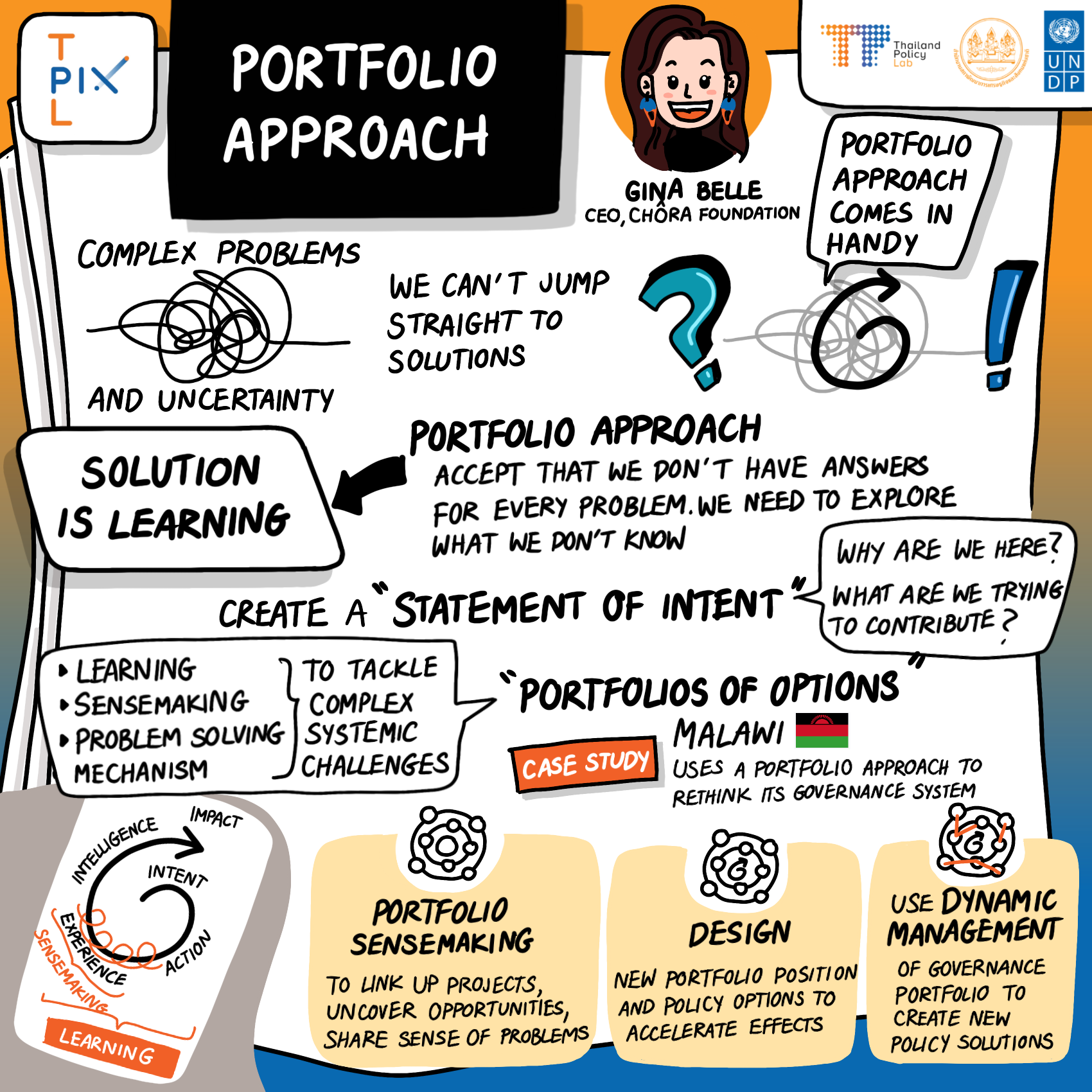

The problems with which policymakers are confronted are far from run-of-the-mill problems; they are systemic, complex, and adaptive. Such policy-related issues often “affect all parts of our lives in all aspects” according to Gina. Further complicating matters is the fact that they often do not behave in linear ways, are time sensitive, and produce unexpected or unforeseen consequences. These issues require policymakers to step into the realm of uncertainty where attempts to address such problems in a technical manner are met with failure or the creation of new unintended problems. Despite one’s best efforts to avoid uncertainty, Gina posits that “we like to think of uncertainty as something that is out there—a property of the world which is far from us—but really it is something that every one of us, individually and collectively, experience when we need to make decisions for complex problems.” For Chôra, a portfolio approach is an effective approach to navigate such complexity and resolve uncertainty through learning.

What are portfolio options? – Resolving Uncertainty through Learning

To approach the Portfolio Approach, Gina maintains that policymakers and operators must go against the human instinct to jump straight to solutions, as this can lead to one falling into the trap of incremental responses. This goes to say, that when dealing with complex problems one cannot know the solution from the onset, as the solutions which are often readily available may not actually address the problem in its entirety. Applying single-point solutions which disregard the complexity of the problem can lead to partial solutions which eventuate or exacerbate further problems. What’s more, simple solutions are often designed with a set of assumptions and a paradigm in mind which may have contributed to the problem in the first place.

While the human tendency to err towards what is known—what we are used to using—is something which helps to navigate problems in one’s day-to-day life, Gina notes that such tendencies lead to wayward policies and portfolios. By comparing portfolios to a game of darts, she effectively illustrates that often a set of objectives are identified as targets on the board which one tries to achieve, followed by retrospective evaluations. Similarly, many projects, initiatives, and policies are initiated with a pre-determined sense of what they wish to achieve, or that they are the solution to the problem they are trying to address. Gina is quick to point out that while these solutions may be appropriate in certain settings, they fail to achieve impact when transformation or complexity is involved. Here, continuous and sustained learning must be present from the onset, and not the learning that occurs in retrospect and often concerning matters which were already known or predictable given a certain context.

The world today sees many complexities; COVID-19, systemic disruption to the tourism sector, or climate impact are all notable examples of issues with high levels of complexity, where, as Gina puts it, “We don’t know what we don’t know.” Something which Chôra has seen to be beneficial in such circumstances is to learn before one acts or to integrate learning and action, and this is the central solution which portfolio approaches provide. While learning may seem to be a broad notion to some, what Gina is referring to is the humility to acknowledge that at times there are no direct answers, that at times, “we need to wake up and find a way to say, we don’t have all the answers.”

Portfolios of Options as Adaptive & Learning-Oriented Tools

Under this framework, a portfolio can be equated to an action, learning, and problem-solving system, which was designed to examine, highlight and create new choices, options, and opportunities in a complex space. Note that options or opportunities are interventions, initiatives, or projects which bridge the gap between what is known and unknown. “Options are like explorers; we send them out into the world to bring back things which we didn’t have before. They provide us new ingredients to a meal, but not the recipe or the final image of the meal.” This goes to say that portfolio options provide the basic components or elements that can be used to achieve a difference in a system.

New portfolios can be designed for exploration, or for learning and entering into the space of the unknown, but more often, Gina notes, portfolios are useful for enhancing pre-existing projects and portfolios in becoming more adaptive and learning oriented. “This is a really good way to bring together things which we already have in the system with a set of new learning options, to see what can be done together, to accelerate learning, and transformation.”

How do we use portfolios as portfolio options? – Malawi Case Study

As portfolios are well-suited options for dealing with complexity and uncertainty across a number of fields, Gina chose to contextualize how they have been used by examining their applications in a collaborative project undertaken with the UNDP in Malawi. In this case study, which spanned a period of 2.5 years, stakeholders sought to examine how governance acts as a multiplier of development effects. Chôra collaborated with senior leadership teams, the portfolio team, as well as government and development partners, to implement the three stages of the portfolio approach and equip the Malawi Country Office with new capabilities and bring about changes to their portfolio. “We wanted to use portfolios as learning mechanisms not just intervention mechanisms.”

The Learning Process – From Problem to Understanding & Transformation

Malawi is a country of 20 million people and ranks consistently among the 15 least developed countries in the world. The UNDP has recognised for quite some time that governance acts as a catalyst to development and governance was thus a priority for this nation. As a result, two portfolios were initiated in Malawi to address issues of civil unrest and promote best practices of governance. For Gina and other stakeholders, a clear need was seen in bolstering the coherence and dynamic capabilities of the portfolio, as well as a need for systems learning approaches to enable operators and stakeholders to better understand both the problem and its effects in a new way.

Statement of Intent, Learning Space, Mapping Current Systems & New Policy Options

The team first began by visualising the transformation, with Gina making clear that doing so ensures that everyone is on the same page in recognising the complexity of the intended change and the reason for the change. This visualisation, which Chôra calls a ‘statement of intend’ challenges each stakeholder to reaffirm what they are doing, why they are doing it, and importantly what system transformation effects they are trying to achieve. From this process, 3 main intentions were discovered (1) accountable institutions, (2) engaged civil society, and (3) effective public service delivery.

From here, now armed with a clearer picture of the intends of stakeholders, attention shifted to the creation of a learning space, a visual representation of the current social system, so that all involved are better able to observe on the 3 dimensions or spaces they prioritize. This process allows one to reduce complexity by homing in on the most relevant aspects or dimensions of a system, and in this case, those which were most relevant to the UNDP. Having created such a space through workshops with UNDP staff, they were now better able to map out existing activities within the space, and identify uncertainties (holes, overlaps, or new options/opportunities) to observe and engage key across key dimensions. At this stage, Gina notes, “It’s as if options become acupuncture points, they help us know, where we need to put pins to actually uncover new interactions in the problem space.” In the case of Malawi, the group were able to identify 6 new portfolio options that pushed them closer to the bound of their dimensions and into uncertainty.

Sensemaking and Intelligence Protocols

It is at this stage in learning that reflective processes such as sensemaking and intelligence protocols come into play. According to Gina, questions outside of the usual policy dialogues begin to foster learning as groups seek to identify and engage novel areas and perspectives. Such questions can include:

- Why are we focusing on this particular set of activities at this point in time?

- Are these activities relevant and coherent to the type of problems we are facing?

- How coherent are out activities to our intent?

- How could these activities work together generate learning?

- How well are the activities helping us learn about what don’t know and reflect on how we could be different?

These questions were used to lead structured discussions on a quarterly basis with a diverse group of stakeholders to allow new learning opportunities to surface. In addition, to ‘stretch’ the bounds of what is known, these sessions were conducted from three different perspectives beginning first with the perspective of the UNDP, then at the level of the sector, which allows for cross-sectorial knowledge exchanges, and finally by considering from the perspective of the whole system.

These learning/sensemaking sessions produced a number of outcomes. The first of which was concerned with capability. By the end of the year the sense that portfolios must be dynamically managed to support change had been firmly embedded into the country office, as this allows them to be more agile in their approaches while making use of innovative tools like sensemaking to iterate and learn. Gina concludes, that while several other outcomes were obtained, perhaps most important among these were the several new policy options which specifically target governance and system transformations across prioritized dimensions in Malawi, making way for more adaptable, and appropriate portfolio management.

Conclusion

In a world where complexity and uncertainty appear in many different forms, our ability to identify the levels of complexity is paramount to formulating an appropriate response. Be it straightforward solutions for technical issues, or adaptive challenges that require system transformations, all challenges present policymakers with the opportunity to engage, learn, and create something unique and impactful. What emerges from the portfolio approach is an important opportunity to learn while engaging systems, engaging uncertainty, identifying new options, and catalysing change across social systems. The need for such changes has been made clear in the face of novel challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change, which present policymakers with the opportunity to learn from and enhance the impact of policies at the national, regional, and local levels.