Speaking at Thailand’s first event to bring innovators and policymakers from around the world (PIX), Joshua Polchar, the Strategic Foresight Lead at the Observatory for Public Sector Innovation (OPSI, OECD), broke down the meaning of the anticipatory approach in an oration entitled “Strategic Foresight in Policymaking”. As an organisation which seeks to engage, investigate, experiment and suggest, the Observatory for Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) serves to enhance public sector innovations found across the world and especially in the 38 member-nations of the OECD.

Strategic Foresight – The OPSI Way

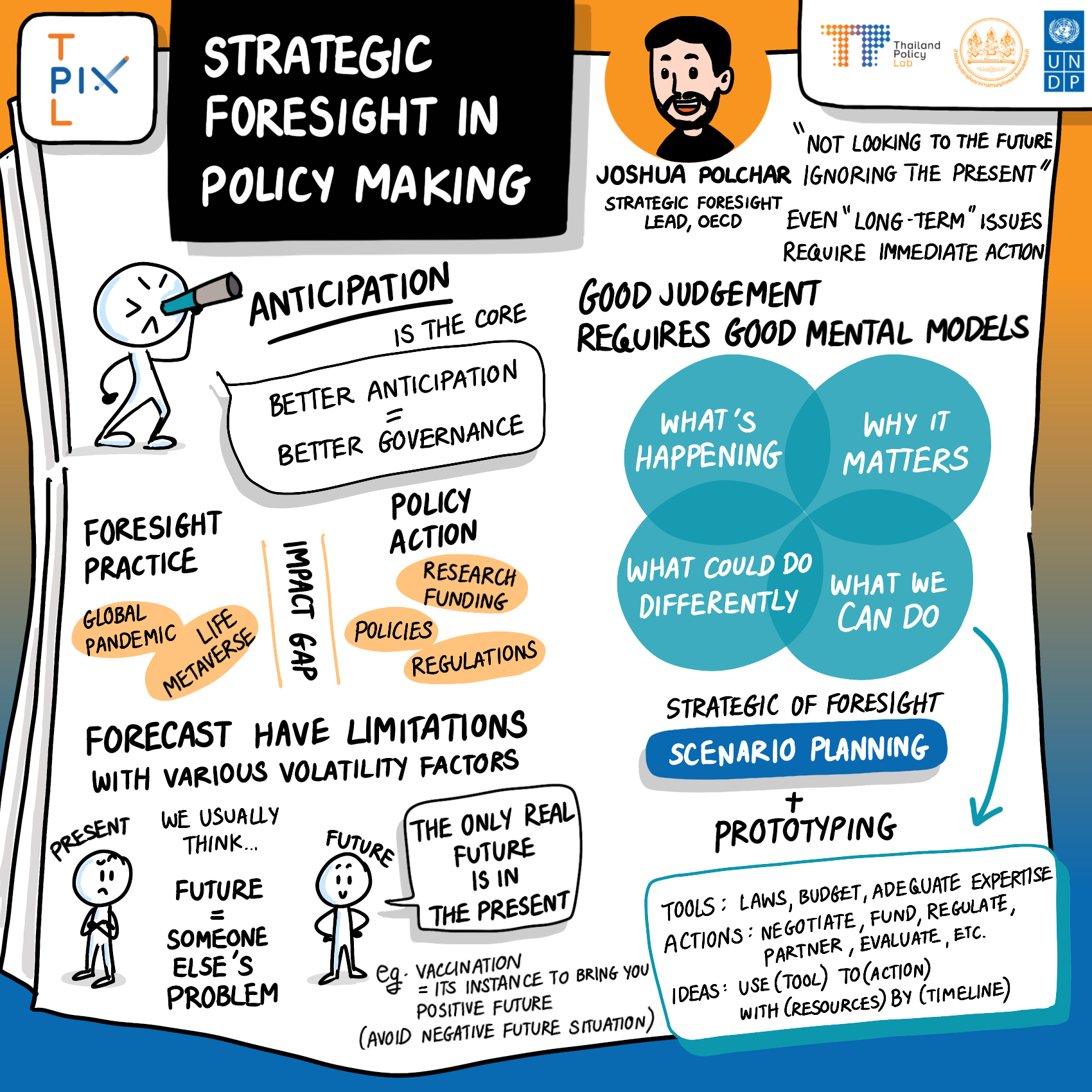

At OPSI, and specifically in Joshua’s team active in strategic foresight, they recognize that “All governments are anticipating all the time but none are making the most of the present to prepare for and shape the future.” To address this point, and so as to produce policy which addresses issues in a more future-forward manner, Joshua indicates that anticipatory innovation serves an important role in shaping and preparing for the future, as opposed to waiting, and passively accepting the future as it happens. To adopt an anticipatory approach to policymaking is to better anticipate necessary adjustments to social governance which ensures a correspondingly better future well-being.

Over the many projects and initiatives co-created with Joshua and organisations, teams, and even policymakers, Joshua has seen 4 key areas where such policies are frequently used, namely (1) stress testing current policy frameworks in various scenarios, (2) developing early warning systems which allow policymakers to get ahead of some of the changes which are occurring the present, (3) envisaging new solutions, which otherwise may have been overlooked, and (4) building a sense of common purpose, where the future represents a shared space for all.

Present Problems: The Impact Gap

Yet, despite remarkably prescient literature and policies which are actively geared to future or anticipatory policymaking themes, when considered collectively, a gap still exists, where on one side one finds published literature and active foresight strategies and other the other side, the policy actions/concrete realisations of thereof. “The problem is not that strategic foresight is not coming up with useful things for governments to consider; the difficulty is using the knowledge generated and turning it into policy action—concrete policies, regulations, laws, or partnerships that governments do all the time; these stand to be enhanced by anticipatory innovation.” For Joshua, to bridge this so-called impact gap, or the gap which exists between foresight and policy implementation, one must engage anticipation, anticipatory innovation, and anticipatory innovation governance mechanisms. These facets to bridge the gap exist in a feeding relationship, where the results or insights gained from one area are taken as inputs to the next in line. Furthermore, certain factors have been found to be conducive to facilitating an environment in which such processes can take place across authorising environments and promotion of agency. To those at the OPSI, these three concepts are defined as follows:

- Anticipation

The creation of knowledge about the future, drawn from existing contextual factors, underlying values and worldviews, assumptions, and a range of emerging developments

- Anticipatory Innovation

Acting upon knowledge about the future by creating something new that has the potential to impact public values

- Anticipatory Innovation Governance

The structures and mechanisms in place that allows and promotes anticipatory innovation to occur alongside other types of innovation

With so much focus being dedicated to the future and anticipating possible scenarios or results which could compromise existing policy frameworks and infrastructure, it is logical to question whether a truly anticipatory approach favours the future over the present, or worse yet neglects the present entirely. Joshua was quick to dispel such notion in clearly stating that “We often think of the future being somewhere else, or someone else. Psychologically, this distances us from the future, making it someone else’s problem. This is dangerous and risky, as we know that your future self is here, in the present.”

Anticipating the Future is a Part of Life

This point finds truth in activities that many have just recently experienced, such as vaccines—this is a present action which influences and protects against negative consequence in the future. Take, for example, dental hygiene routines, where, arguably, most all humans know that oral hygiene is important as it stands to bring us positive future benefits while minimising the potential for unwanted or negative consequences and this is at the core of the anticipatory approach. Despite the oversimplification, it stands to reason that anticipating the future is a human tendency and furthermore, that it is one in the same process with anticipatory approaches to policymaking. For those at OPSI, this extends to even very distant future, or to systems with far-reaching goals, such as the SDGs, where common goals or anticipation thereof prompts present action.

According to Joshua, the “only real future is in the present.” The future is always and only emerging in the present, and so, to anticipate the future, one must explore, understand, and act in the present. In terms of the types of actions, or tools, which can be used to anticipate the future for policymakers, a number of tools have been applied to this area and include, forecasting, speculating, scanning, expecting, modelling, and planning, the majority of which are well-known to policymakers. Yet, action must be taken in the present, as anticipating in the future can be called “too late” according to Joshua, who always supports being vigilant of possibilities in the future and exploring them in a dialogue with others. “This dialogue between stakeholders, between times is what the anticipatory approach is all about,” says Joshua, who notes that anticipatory approaches recognise that collective action must be taken to affect the future.

Volitility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Novelty in the Future

Despite the hopeful message, and great strides which can be taken to collectively preparing for the future, Joshua is quick to point out that the future is difficult, if not impossible to predict. There are many unknowns in the future, and the future, is a volatile, uncertain, complex and novel realm, where it is impossible to anticipate or know all. From overestimations of the effects that new technologies will have, e.g., AI taking over everyone’s jobs within X years, or the inability to accurately predict up-and-coming consumer fads, divergence in opinions and incongruence between what was expected and what happened are to be expected. Based on arguments and examples as above, Joshua concludes that, as an evidence-based organisation, the evidence base will always be incomplete. Yet, here lies the challenge set out before policymakers, as one cannot wait for the evidence to be complete, as this will be too late to have been too late. Examples of this can be seen in many sectors but can be exemplified in the missed opportunity of certain mobile phone manufactures, who neglected to consider evidence that disruptive touchscreen phones could be explored and continued to produce keyboard-based phones until it was too late. With hindsight, it is clear that they were too slow to identify changes, to identify opportunity. To OPSI, strategic foresight therefore refers to the ability to constantly perceive, make sense of, and act on the future in the present. Such goals can be accomplished by leveraging anticipatory innovtaion, or the process of acting upon knowledge about the future by creating something new that has the potential to impact public values.

Don’t Know; Prototype, Anticipate, and Act

As much of the future will always be unknown, organisations such as OPSI seek to achieve adjustments to organisational mindsets from being reactionary to being anticipatory. They promote engaging simulations, scanning for opportunity, and actively collecting in data and knowledge which make organisations better able to anticipate. This process often begins with the process of prototyping. “This process is very messy, and it often produces unusable or ugly results. But when you do it again and again you begin to fall into a rhythm of good judgements.” Ultimately, it allows individuals and organisations to build up their capacities and ability to identify possible tools, actions, and ideas that can be operationalised for different scenarios. As this represents an iterative and repeatable process, often times the components of the plan become increasingly clearer with each iteration, such that many organisations across the world have made use of this to modify their mental models and approaches to future readiness.

According to Joshua, one of the biggest challenges to organisations in all sectors is the psychologically limiting mindsets they promote. While acting on knowledge is ideal, it is rarely the case, and when presented with such instances, most employees, staff, and officials tend to pull away. This should be the moment where we all investigate further, try to progress the concept to scenarios, build prototypes to address these scenarios, and iteratively identify possible outcomes. Importantly, Joshua concludes, this process is a dialogue, and should involve as many people as possible, as “expertise may come from areas or sources of knowledge that we didn’t expect.”