The Thailand Policy Lab staged Thailand’s first Policy Innovation Exchange (PIX) on 24 November 2021, which brought together more than 10 thought leaders and innovators from across the globe. While host to many of the world’s forerunners of innovation and policy, opening contributions and an introduction to what was in store was delivered by Kate Sutton, the Head of the Regional Innovation Centre, UNDP, whose expertise across the fields of entrepreneurship, international innovation, and policymaking, allowed her to broadly introduce key concepts and processes for audience members.

Trouble in Paradise: Policymaking Challenges

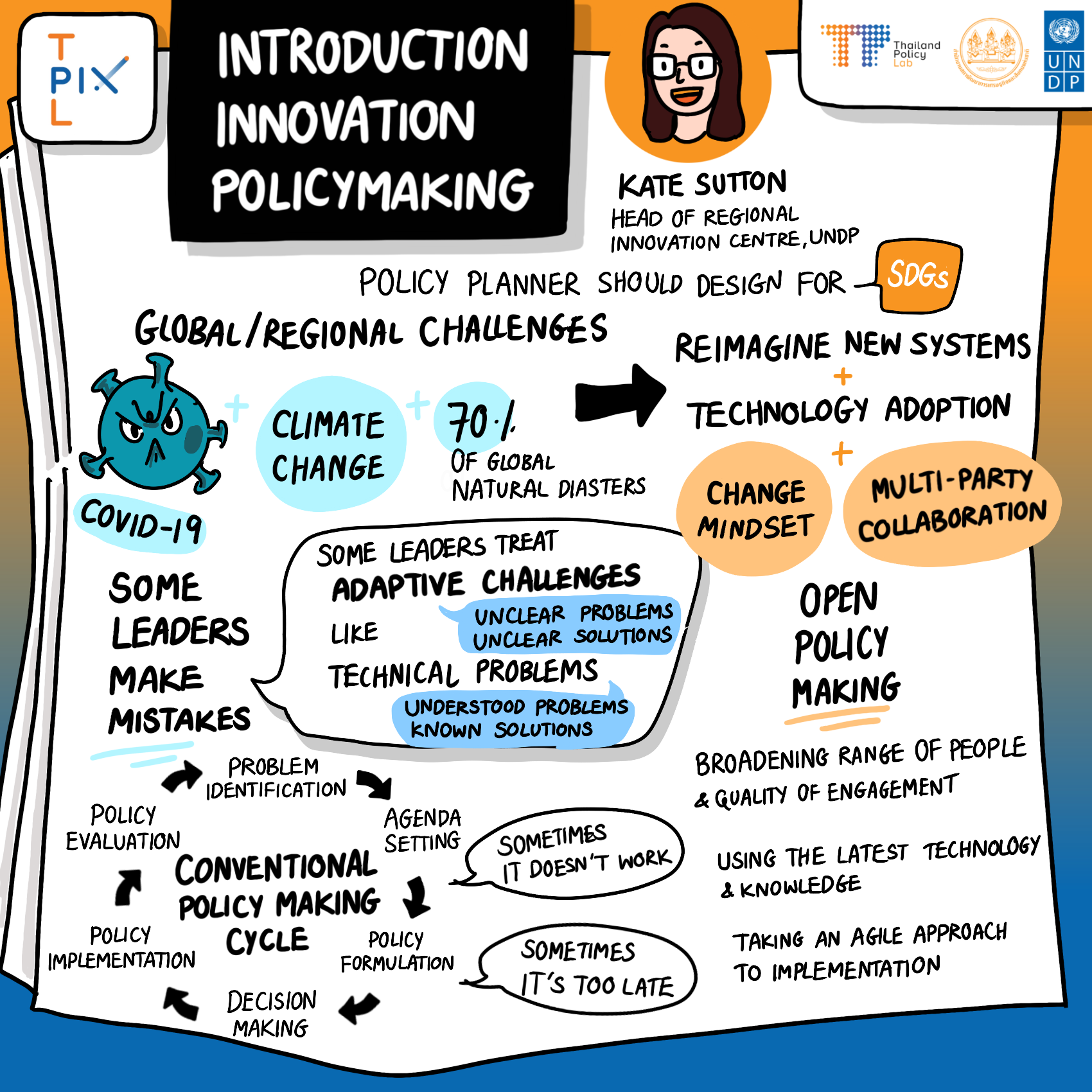

As the head of a team of regionally active innovators comprising some 35 nations in the APAC region who spearhead projects to bring SDGs to fruition, Kate is aware of the challenges that policymakers face. Citing challenging circumstances such as the Covid-19 pandemic, and global climate change, Kate set the stage by reinforcing the importance of integrating innovative approaches to policymaking. “Now more than ever, in the face of many crises, we need to explore, examine, and integrate policy innovation and new ways of doing things.”

Specific to the APAC region, she identified a number of challenges faced by the region in achieving policymaking goals, including: COVID-19, the climate crisis, higher than usual natural disaster prevalence, challenges to handling rapid urbanisation, widening income/wealth gaps, and notably, geopolitical turmoil. Yet, despite the confluence of regional factors which impact the region and despite lacking more than half of the technology required to innovate past these hurdles, she remains positive that we all stand to benefit from adopting a shift in the way that policies are made. This shift requires us to reimagine and transform systems at a fundamental level—“Often, we don’t want to be looking for a single point solutions, because that’s not what’s needed. We need to be more agile, and more anticipatory in our policymaking approaches.”

Adaptative Challenges vs. Technical Problems

For Kate, many of the issues we face today are beyond the scope of so-called technical problems and should be treated as adaptive challenges. Technical problems, e.g., installing plumbing in one’s house, or installing solar panels, are easily understood, and have simple, often straightforward solutions that can be addressed with a matter of expertise, time, money, or other pre-existing resources. Such problems can be resolved by bringing experts and authorities together to develop plans, implement these plans, allocate inputs, and measure results.

This differs from the more “nuanced, systemic, stubborn, and persistent” challenges one encounters with adaptive challenges. Adaptive challenges present policymakers with unclear and often shifting variables, which require some level of learning in order to adequately understand them. These problems adapt and morph into new problems with consequences that could not be foreseen within a technical scope, and with effects that often do not wait for results of decisions. What’s more, with adaptive challenges, solutions are often unknown, and cannot be resolved by simply consulting authorities or experts—the uncertainty and complexity of these challenges requires a more thorough approach to stakeholder engagement to overcome obstacles and understand values, loyalties, assumptions, and prejudices. Take, for example, the questions of how best to revive the tourism industry in Thailand in a sustainable manner? The sheer complexity of such questions certainly requires the input of experts and authorities, but it also requires a more anticipatory approach to truly understand the roots, and subsequent growth and setbacks of involved stakeholders. To begin to understand such a challenge, one is required to question the assumptions, processes, and the needs of those involved. For policymakers, this can mean questioning our former intuitions and practices, as well as identifying news ways of accomplishing goals, all while learning adapting.

Adaptive Challenges as the Impetus to Systemic Change

For Kate, approaching adaptive challenges means moving away from the unempowering policymaking loop of identifying, setting an agenda, formulating, decision making, and pushing out policies without careful regard and consideration of how the problem is reacting to policy or how the people’s needs may have changed through this process. According to Kate, adaptive challenges present us all with the opportunity to marry complex social problems with missions and goals at higher levels. Take, for example, the work of the UNDP in tackling plastic consumption problems in Vietnam, which is used as a portfolio project to support the greater mission of realizing a circular economy. This example, much like tourism in Thailand, is complex, and can be handled with use of new skills and learning abilities such as horizon scanning, signal/noise sensing, and more generally by being adaptable and agile.

While many innovative tools are not new per se, they may be new to policymaking and thus require an entrepreneurial spirit and innovative mindset. To tackle such uncertainty in a meaningful and powerful way, Kate feels that a paradigmatic mindset shift is required. Such a shift sees civil servants approaching their roles with humility, and looking for new methods of engaging people, while learning from their adaptive and agile experiments. Kate considers the measures taken by organisations such as NESDC and the work undertaken by the Thailand Policy Lab to be laudable; “It’s the NESDC’s permission to explore and to try and do things differently, which really speaks to their willingness to recognise the issues in society on a deeper level and engage them in a new and interesting way.”

Conclusion

In the conclusion of her introduction, Kate stressed that in order to tackle adaptive challenges, many changes must take place, but salient among these are the need for iterative applications of learning and measuring. From resource identification to stakeholder engagement, from formulating approaches to issuing mandates and policy creation, regardless of the stage all stakeholders in the policymaking process must “embody the spirit of experimentation and integrate learning at the core of their framework.”

Moving forward, policymakers must recognise the complexity of the challenges with which they are faced as well as the need to explore the inkling that the way we do policy needs to change. “Be an early adopter; be a champion for the fact that the current way of doing things is frustrating.” This does not go to say that the old ways should simply be scrapped—quite the opposite—the purpose of integrating innovation with policymaking is to bolster policymaking toolkits to better anticipate and handle novel and complex adaptive challenges. Here, the focus is on recognising the potential to create something new, which holistically addresses the complexity of challenges while envisaging a new way of policymaking where no one is left behind.