There are things that come to mind when we talk about Audrey Tang: the fact that she is Taiwan’s youngest minister without portfolio, and the first transwoman with leadership in the Executive Yuan. Prior to her ascendancy, Tang, however, had neither experience in government affairs nor public policy. Her work is deeply rooted in the civic technology movement, whose goal is to make the government more “open.” Tang’s rise to the Executive Yuan is not just a personal achievement, but a reflection of Taiwan’s political landscape, actively shaped by the ordinary with change-making means in their hands. Let’s take a look at how Taiwanese people participate in governance and social transformation so far.

From deep-seated distrust of the government, to collaboration with state agencies

One of the most outstanding collectives in Taiwan is “g0v,” a civic tech community that “pushes information transparency, focusing on developing information platform and tools for citizens to participate in the society.” Currently, the g0v community has initiated various projects in support of the government’s existing works. Such examples include the “Moedict,” or the community-maintained version of the Ministry of Education’s online dictionary, and “vTaiwan” (virtual Taiwan), an open consultation process intended to expand citizen’s opinion-sharing space as much as possible. Yet if we circle back to the origins of g0v, it is clear that their stance towards the government is far from cordial. The seeds of their call for civic engagement is distrust of authority, to the point that resistance becomes the right response.

Back in 2012, the government under Ma Ying-jeou’s leadership released a propaganda video titled “What is the Economy Power-Up Plan?,” in which the following sentences were repeated over and over: “we have a very complex plan. It is too complicated to explain. Never mind the details–just follow instructions and go along with it!”

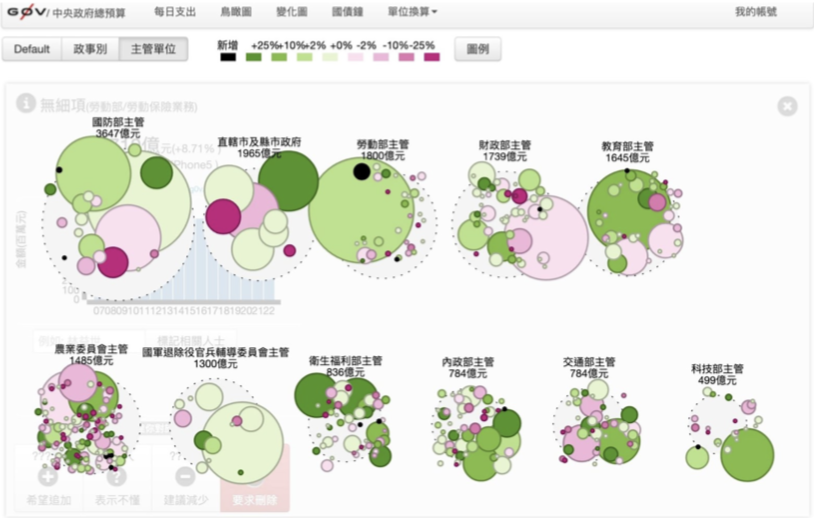

That propaganda video was also released at the time Yahoo! Open Hack Day was held. A group of Taiwanese participants then came up with a last-minute project: Budget Maps. Each government project is visualised as a circle that expands or shrinks in proportion to the amount of budgets spent on it. In this way, the distribution of budgets is laid bare to the viewers’ eyes, and they can decide for themselves which project deserves funding, or needs to have its budgets cut down (such as propaganda videos).

>>>Click here to see the Budget Maps.

Since then, the ethical hackers formed g0v, a space that welcomed all like-minded individuals, regardless of their academic and professional backgrounds. A “hackathon” would be held bi-monthly for members to present their proposals about civic engagement projects and recruit more helpers. More experienced members would provide feedback and recommendations that potentially shaped ideas into a reality. Projects that received endorsement would be eligible for “Civic Tech Prototype Grant,” sponsored by NGOs, tech groups, and media agencies.

Until now, g0v has received more than 839 proposals. The article will focus on vTaiwan, as it shows the reality of putting the principle of open government into motion.

vTaiwan: not an innovation, more about listening and opinion-gathering sessions on a national level

In 2014, Taiwan’s pursuit for democracy intensified as the Sunflower Movement occupied government buildings in protest of the trade pact with the People’s Republic of China, considered by many as the potential threat to Taiwanese sovereignty. G0v members, including Audrey Tang, joined the occupation, providing basic internet access in places without internet networks. It was this year that the g0v community would also step up to democratise governance with their creativity.

From 2012-2014, the government faced serious allegations of corruption. As a result, the public trust in the authority gravely deteriorated. “Jaclyn Tsai,” the digital ministry at that time, attended a hackathon with one challenge for g0v: make a consultation process accessible to the entire country. Tsai ceded complete control over the project to g0v, claiming that “the government doesn’t know how to do this. You guys [g0v] figure it out” (Tsai also appointed Tang as her assistant. In 2016, Tang took over the position of digital minister.) The g0v community then designed the open consultation that covered a wide array of stakeholders, from high-ranking officials to laypeople, opening up the possibilities for everyone to feed into policy recommendations and find consensus together.

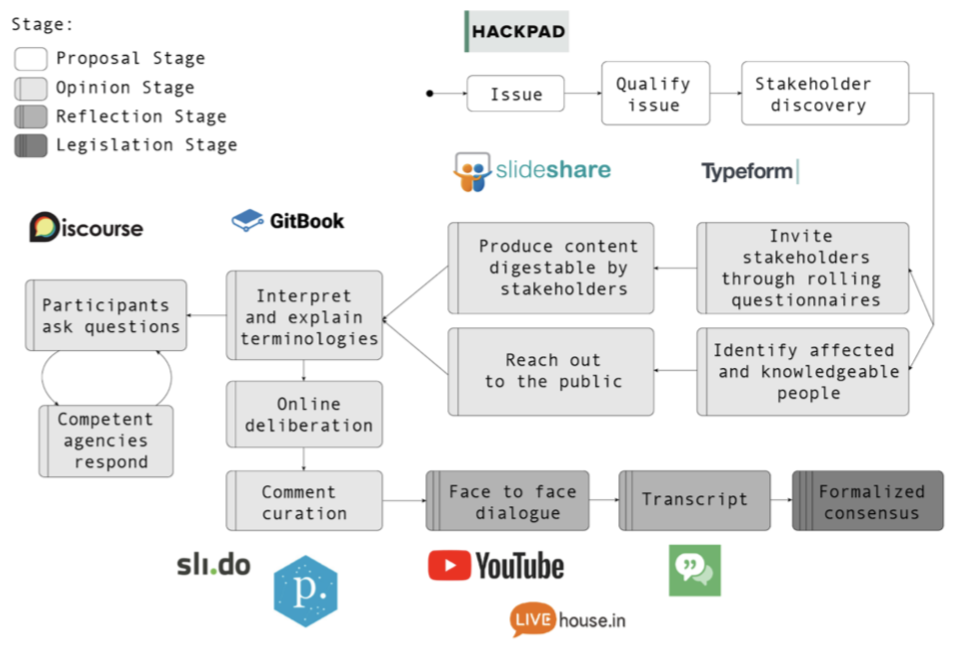

To summarise, vTaiwan is divided into 4 steps:

- The proposal stage: organise a mini Hackathon for discussions. Selected issues will be submitted for the consideration of the government and vTaiwan’s facilitators.

- The opinion stage:

- Release relevant documents to the public along with lexicon to avoid confusion of meanings.

- Invite participants to take “rolling questionnaires” about their knowledge and experiences with selected issues as well as recommended stakeholders.

- Encourage participants to submit their questions to the designated platform called “Discourse.” Each ministry, represented by their “Participation Officer,”is bound to give answers within 7 days.

- Facilitators kick off discussions among participants, who are tasked to vote “Agree,” “Disagree,” and “Pass” or make other statements.

- Use “Pol.is,” a machine learning software, to visualise the ongoing landscape debate by depicting the mainstream and non-mainstream opinions, and potential consensus among conflicting ideas.

- Provide a summary report of the opinion stage to state agencies.

- The reflection stage: hold livestream sessions of meetings among facilitators, experts, key stakeholders, and state agencies.

- The legislative stage:

- Summarise the debate and progress of discussions.

- Identify consensus in the landscape of opinions, and develop guidelines and public policy based on it. If the parliament rejects the recommendations, it must fully disclose the reasoning behind such a decision to the public.

The 4 steps of open consultation. Image: vTaiwan.

Participedia, the database for participatory citizenship, reveals that more than 30 issues, principally those concerning digital economy, have made their ways into vTaiwan, with prime examples being the regulation of Uber and FinTech sandbox policy.

However, vTaiwan is far from being the process that truly embraces the entirety of the nation. Participedia notes that, despite the overwhelming numbers of 200,000 members in vTaiwan’s mailing list, not everyone shows up or attends mini Hackathons with the same frequency. Furthermore, the possibility of leaving marginalised groups out of the discussions remains high, as only those who attend mini Hackathons can submit their concerns to vTaiwan facilitators.

As there is no universally applicable model, the “success” of participatory citizenship in Taiwan cannot be replicated in other places. Eliza Barry, Director of Public Laboratory for Open Technology and Science, remarks that Taiwan shows the world how to “reclaim the democratic process for including the people’s voice in creating laws,” meanwhile participatory legislation in other countries fell short. For example, Iceland attempted to make a crowdsourced constitution, establishing a council of constitutional drafters without politicians and allowing citizens to comment on the constitution via social media (over 3,600 commentaries and 360 recommendations were made during the review period). However, the parliament decided to kill the draft constitution. Katrín Oddsdóttir, human rights lawyer, described this move by the parliament as the rejection of change by the systems.

As of now, the g0v community still plays a significant role in developing civic technology for citizens and the public sector. If there is one thing this collective can teach, it is to challenge the authority with whatever means you have, however you can. Get together, force the government to be better, just like what the g0v’s motto says: ask not why nobody is doing this. You are the “nobody”!